“In this world of over-production and the dominant culture of growth for the sake of profits and not much else, we have turned our attention to the idea of slow and careful nurture. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, nurture is ‘the process of bringing up or training. It is also about feeding and offering nourishment.”

Hole & Corner Magazine ~ Issue 23 Nurture

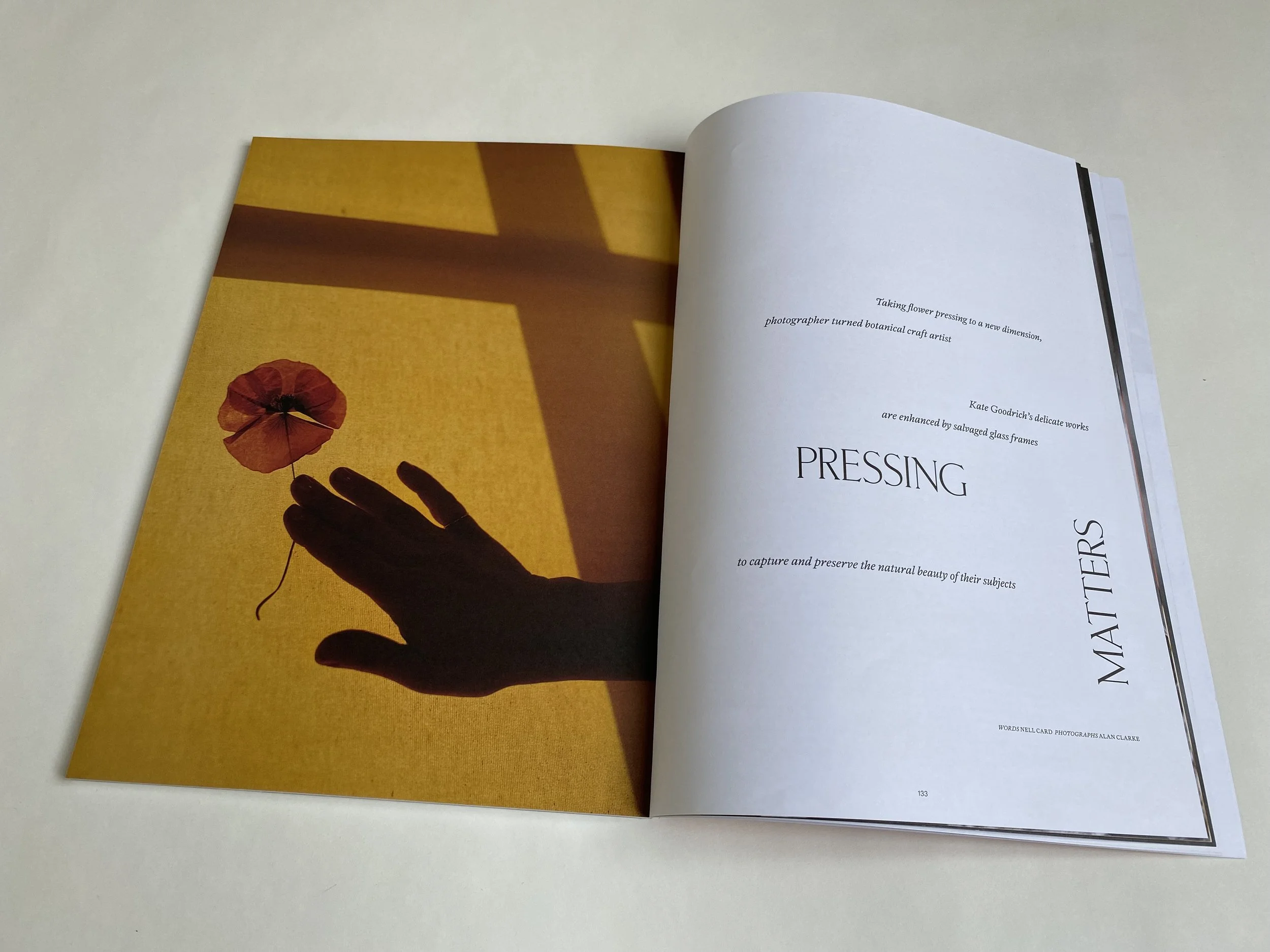

Photographs by Alan Clarke Words by Nell Card

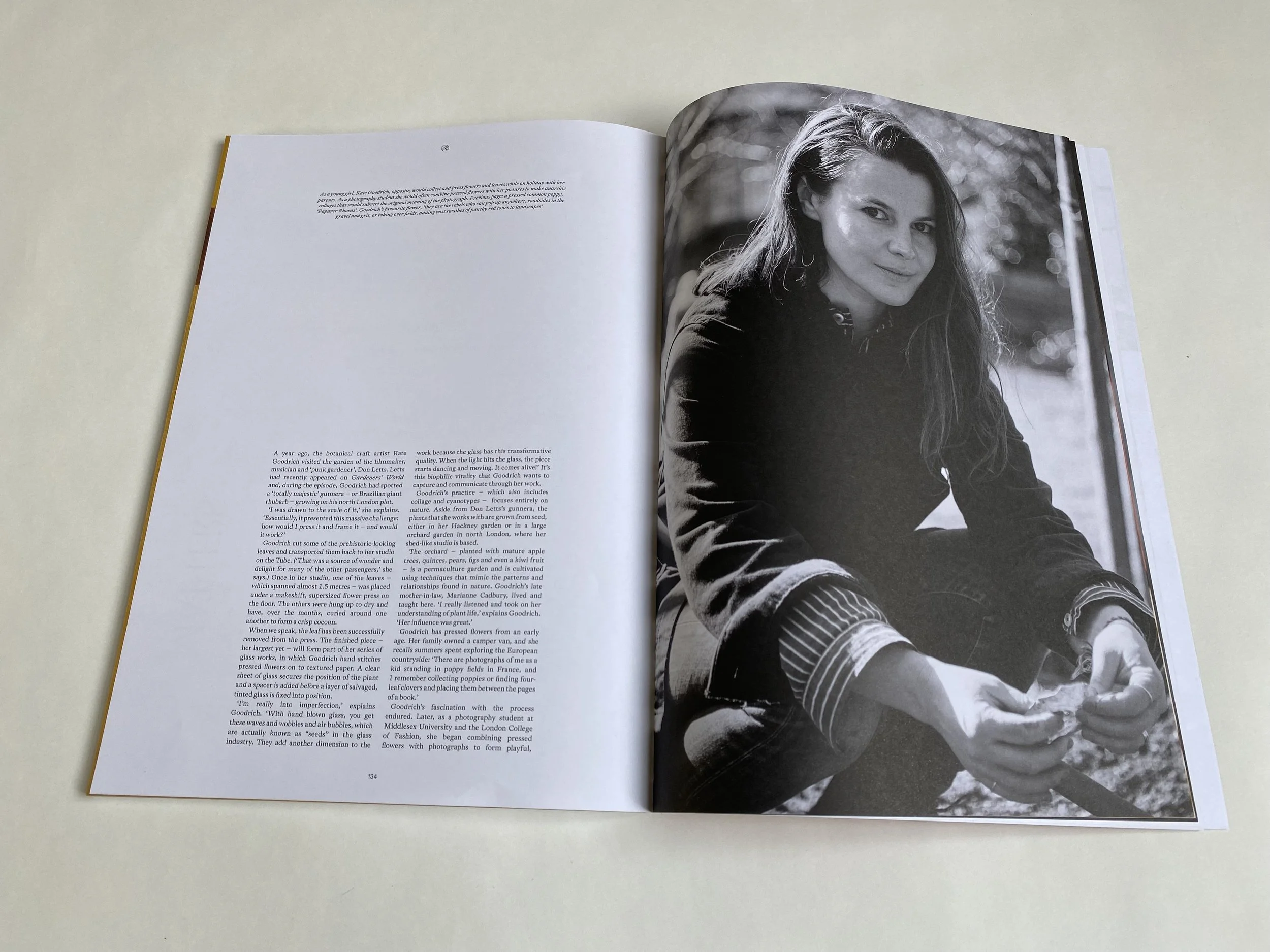

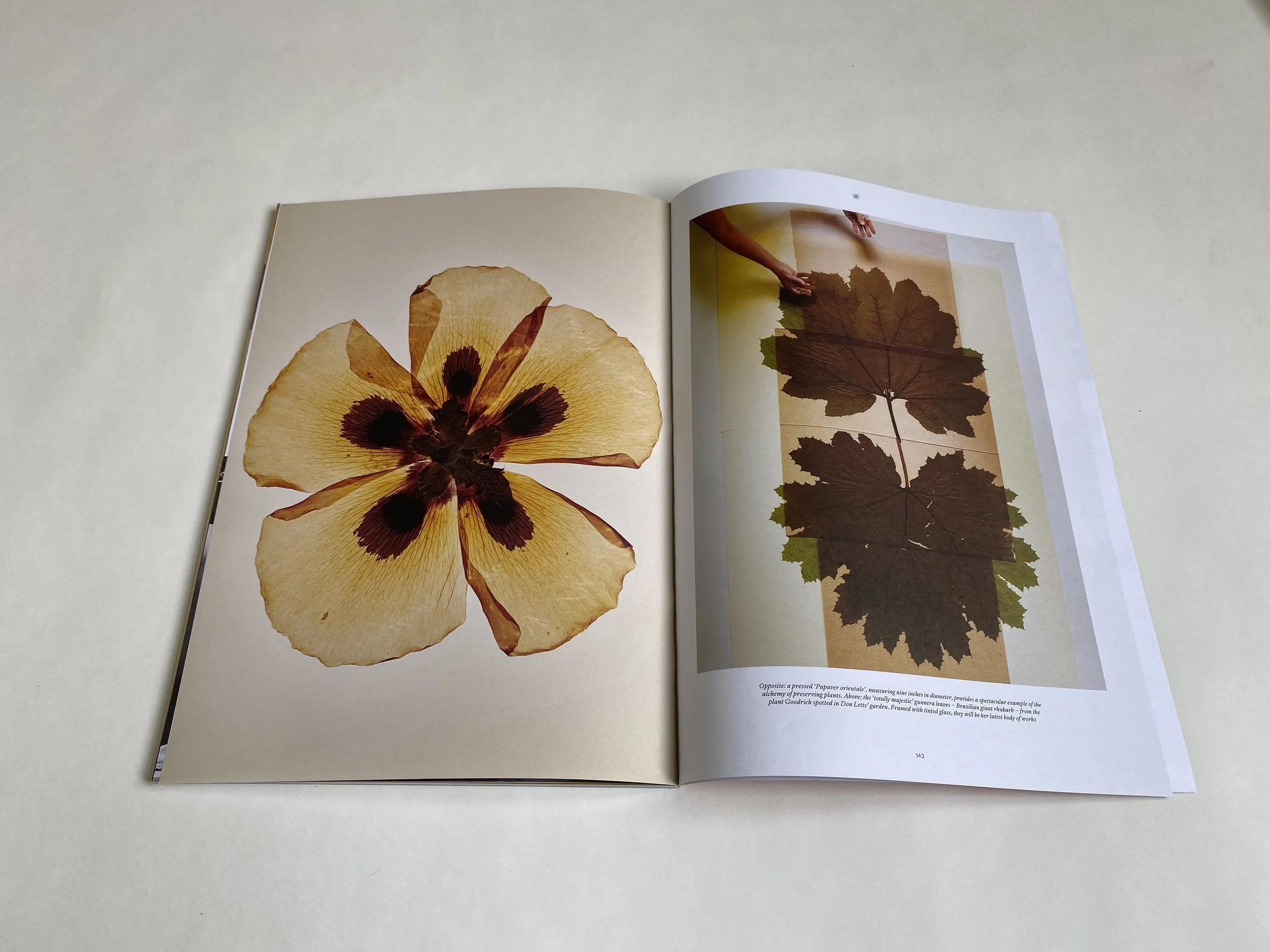

A year ago, the botanical craft artist, Kate Goodrich, visited the garden of the filmmaker, musician and “punk gardener”, Don Letts. Letts had recently appeared on Gardeners World and, during the episode, Goodrich had spotted a “totally majestic” gunnera – or Brazilian giant rhubarb – growing on his north London plot. “I was drawn to the scale of it,” she explains. “Essentially, it presented this massive challenge: how would I press it and frame it – and would it work?” Goodrich cut some of the prehistoric-looking leaves and transported them back to her studio on the tube. (“That was a source of wonder and delight for many of the passengers,” she recalls.) Once in her studio, one of the leaves – which spanned almost 1.5 metres – was placed under a makeshift, supersize flower press on the floor. The others were hung up to dry and have, over the months, curled around one another to form a crisp cocoon.

When we speak, the leaf has been successfully removed from the press. The finished piece – her largest yet – will form part of her series of glass works, in which Goodrich hand stitches pressed flowers on to textured paper. A clear sheet of glass secures the position of the plant and a spacer is added before a layer of salvaged, tinted glass is fixed into position. “I’m really into imperfection,” explains Goodrich. “With hand blown glass, you get these waves and wobbles and air bubbles, which are actually known as seeds in the glass industry. They add another dimension to the work because the glass has this transformative quality. When the light hits the glass, the piece starts dancing and moving. It comes alive!” It’s this biophilic vitality that Goodrich wants to capture and communicate through her work.

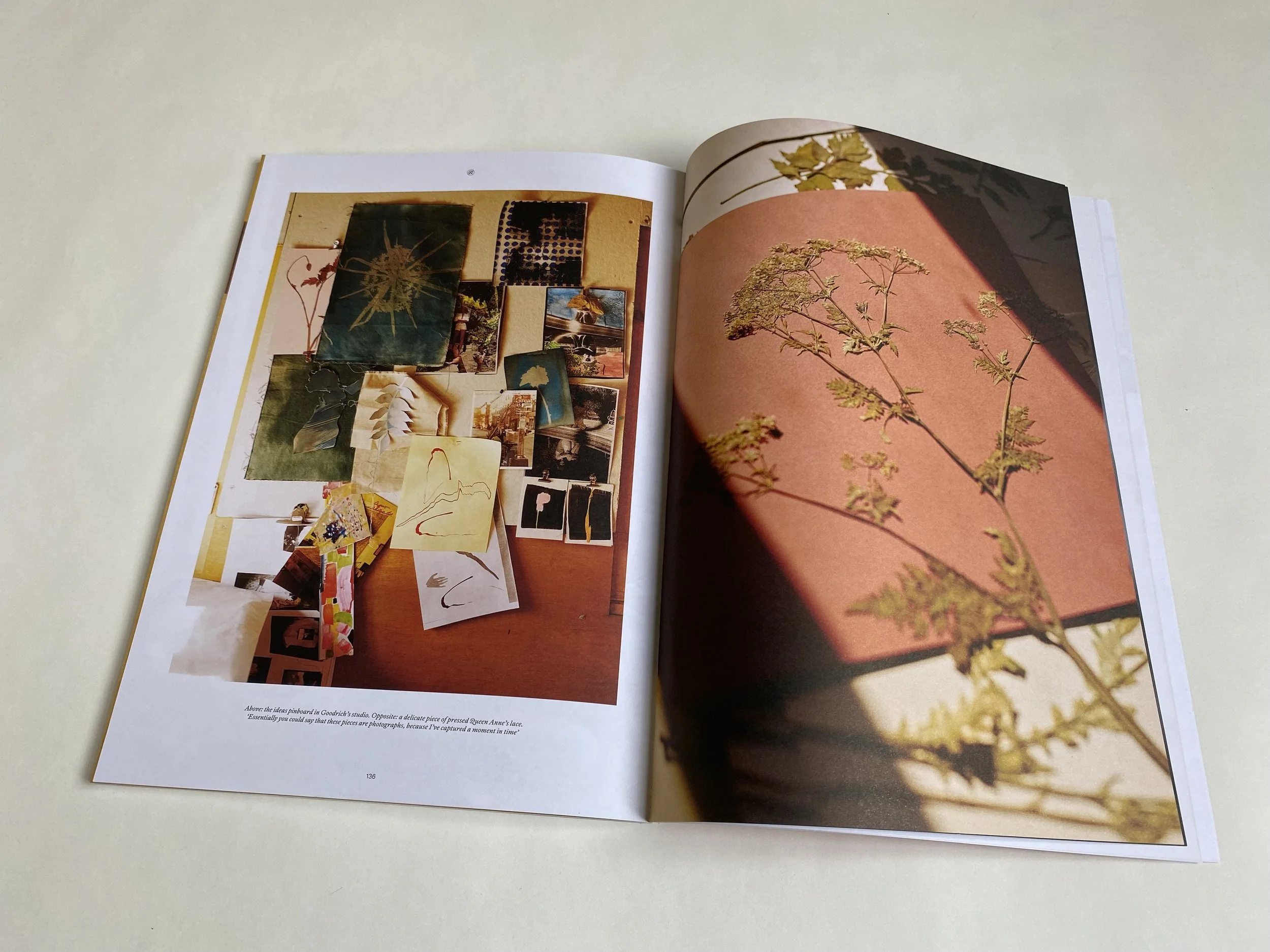

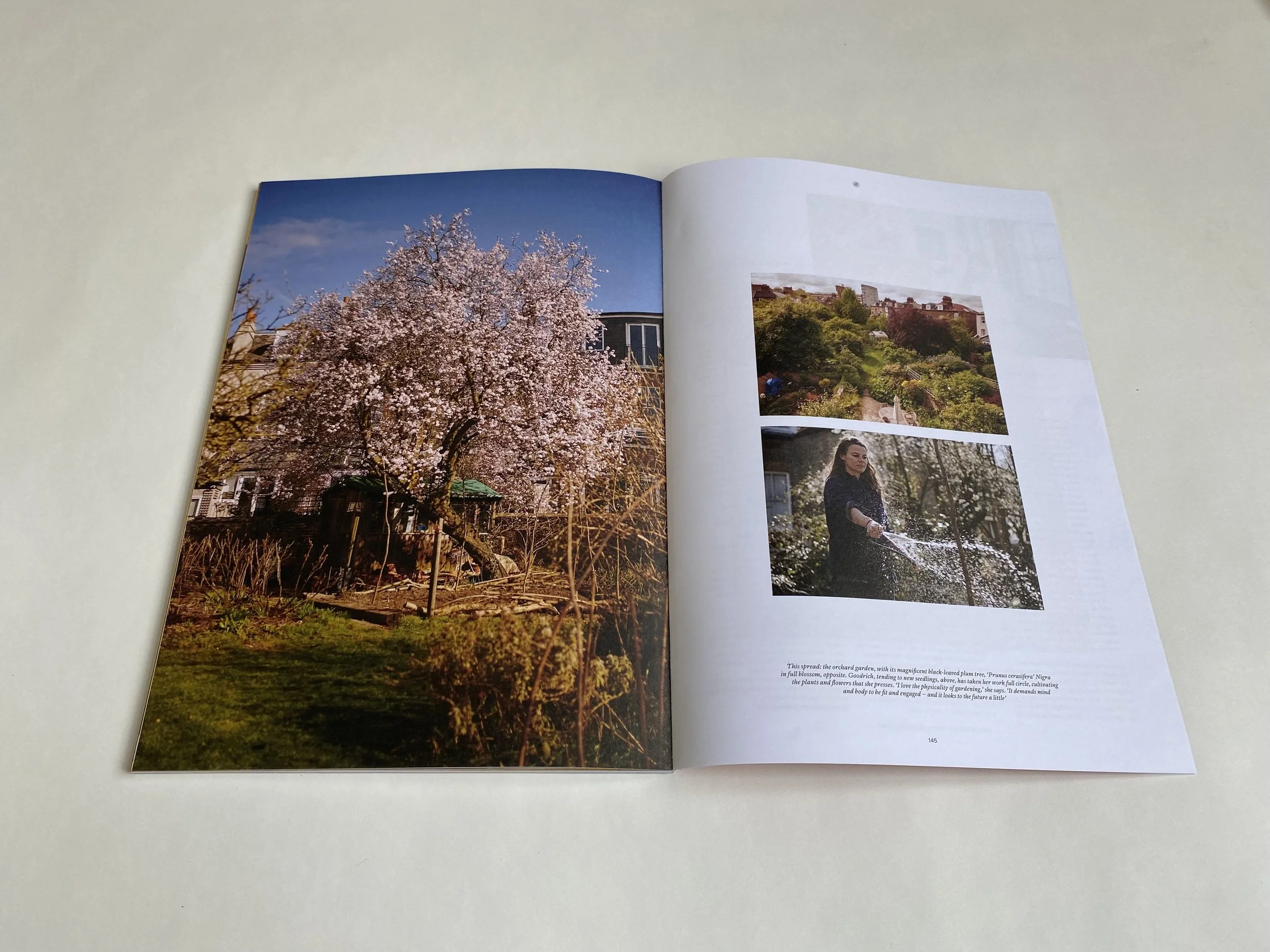

Goodrich’s practice – which includes collage and cyanotypes – is entirely regenerative. Aside from Don Letts’s gunnera, the plants she works with are grown from seed either in her Hackney garden or in a large orchard garden in north London, where her shed-like studio is based. The orchard garden – planted with mature apple trees, quinces, pears, figs and even a kiwi fruit – is a permaculture garden and is cultivated using techniques that mimic the patterns and relationships found in nature. Goodrich’s late mother-in-law, Marianne Cadbury, lived and taught here. “I really listened and took on her understanding of plantlife,” explains Goodrich. “Her influence was great.”

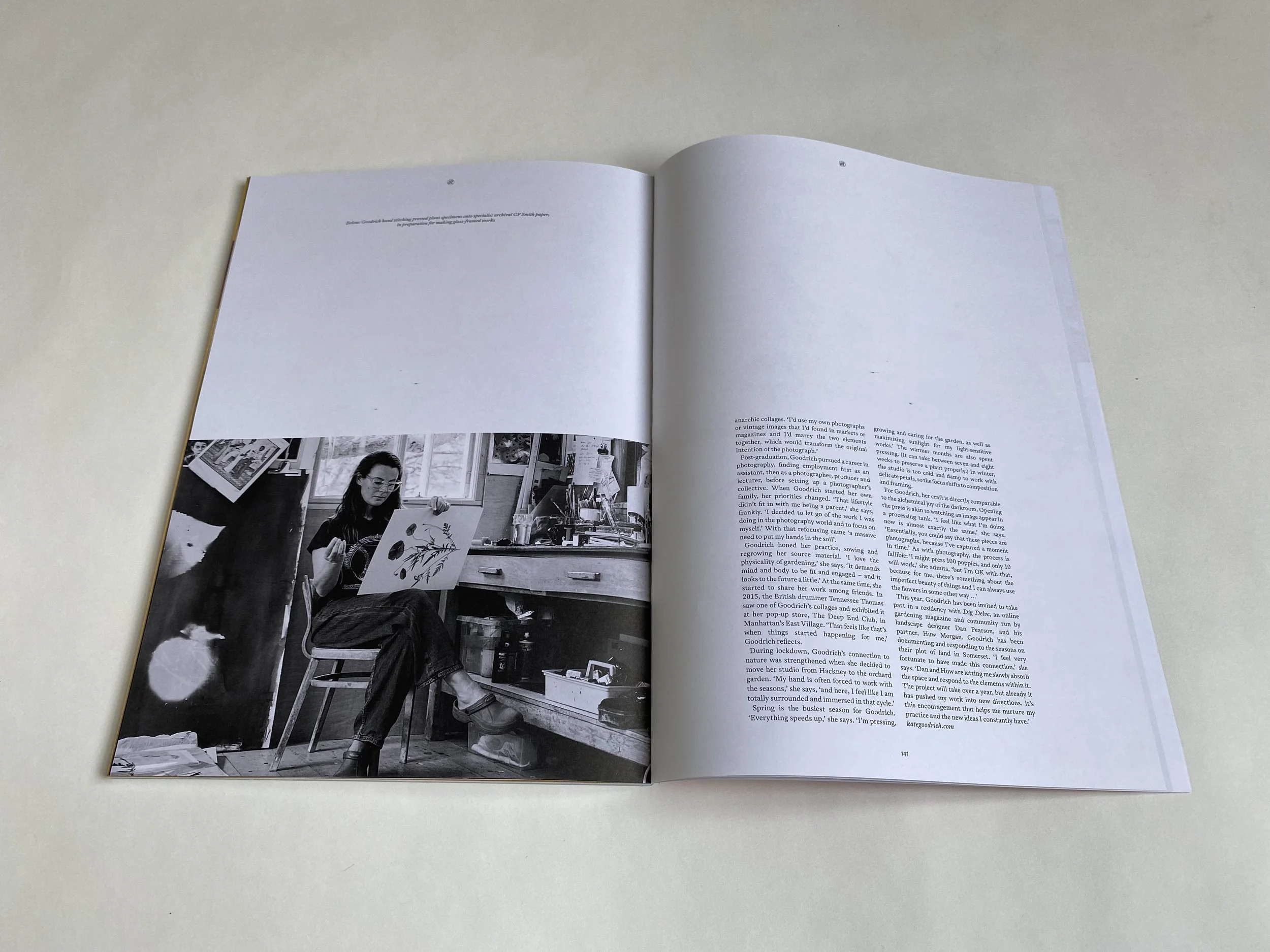

Goodrich has pressed flowers from an early age. Her family owned a camper van, and she recalls summers spent exploring the European countryside: “There are photographs of me as a kid standing in poppy fields in France, and I remember collecting poppies or finding four-leaf clovers and placing them between the pages of a book ...” Goodrich’s fascination with the process endured. Later, as a photography student at Middlesex University and the London College of Fashion, she began combining pressed flowers with photographs to form playful, anarchic collages. “I’d use my own photographs or vintage images that I’d found in markets or magazines and I’d marry the two elements together, which would transform the original intention of the photograph.”

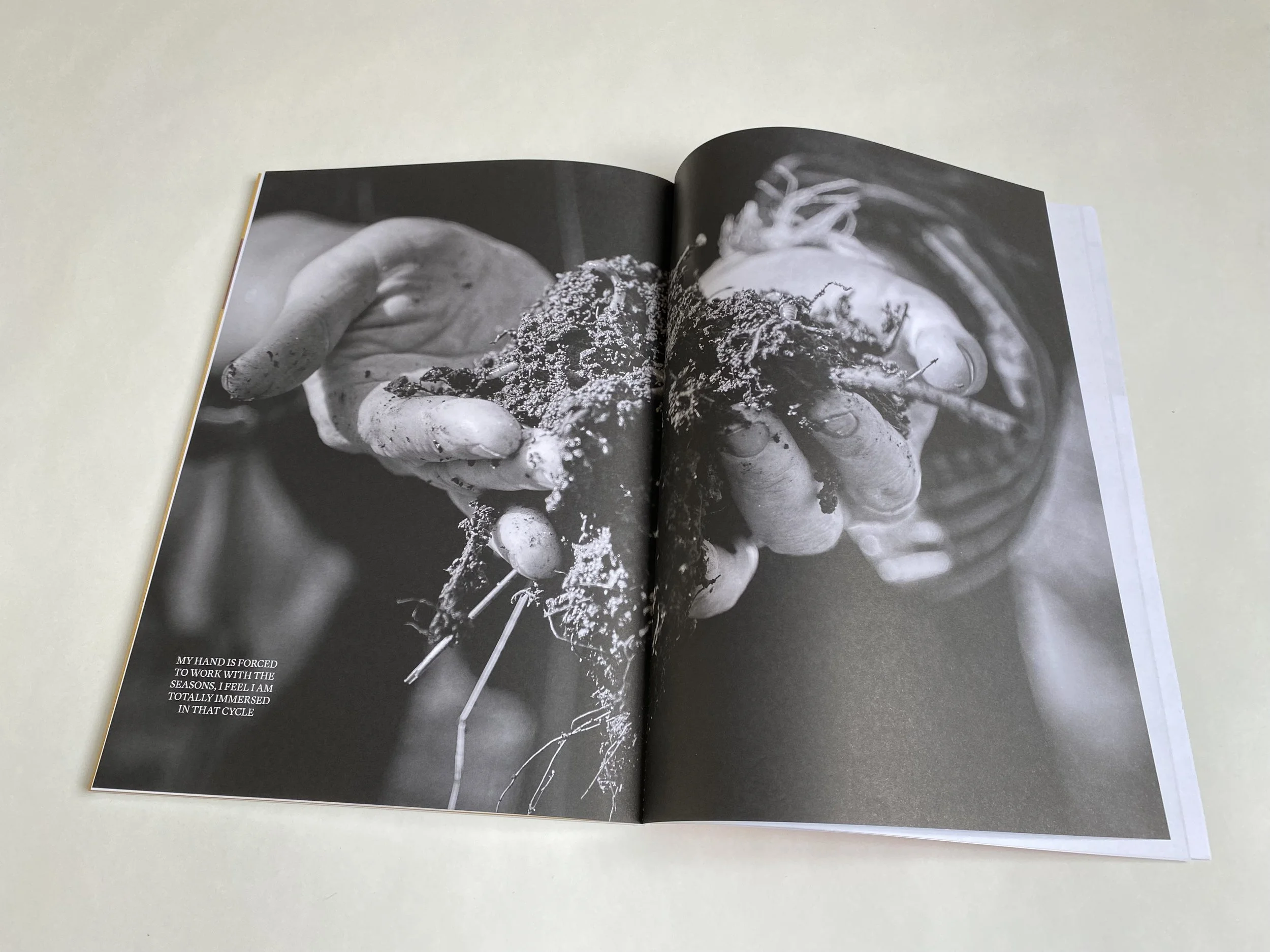

Post graduation, Goodrich pursued a career in photography, finding employment first as an assistant, then as a photographer, producer and lecturer, before setting up a photographer’s collective. When Goodrich started her own family, her priorities changed. “That lifestyle didn’t fit in with me being a parent,” she says, frankly. “I decided to let go of the work I was doing in the photography world and to focus on myself.” With that refocusing came a “massive need to put my hands in the soil.” Goodrich honed her practice, sowing and regrowing her source material. “I love the physicality of gardening,” she says. “It demands mind and body to be fit and engaged – and it looks to the future a little.” At the same time, she started to share her work among friends. In 2016, the British drummer, Tennessee Thomas, saw one of Goodrich’s collages and exhibited it at her pop-up store, Deep End Club, in Manhattan's East Village. “That kind of feels like when things started happening for me,” Goodrich reflects. During lockdown, Goodrich’s connection to nature was strengthened when she made the decision to move her studio from Hackney to the orchard garden. “My hand is often forced to work with the seasons,” she says, “and here, I feel like I am totally surrounded and immersed in that cycle.” Spring is the busiest season for Goodrich. “Everything speeds up,” she says. “I’m pressing, growing and caring for the garden, as well as maximising sunlight for my light-sensitive works.” The warmer months are also spent pressing. (It can take between 7-8 weeks to preserve a plant properly.) In winter, the studio is too cold and damp to work with delicate petals, so the focus shifts to composition and framing.

For Goodrich, her craft is directly comparable to the alchemical joy of the darkroom. Opening the press is akin to watching an image appear in a processing tank. “I feel like what I’m doing now is almost exactly the same,” she says. “Essentially, you could say that these pieces are photographs, because I've captured a moment in time.” As with photography, the process is fallible: “I might press 100 poppies, and only 10 will work,” admits Goodrich, “but I’m OK with that, because for me, there’s something about the imperfect beauty of things and I can always use the flowers in some other way …”

This year, Goodrich has been invited to take part in a residency with Dig Delve, an online gardening magazine and community run by the landscape designer, Dan Perason, and his partner, Huw Morgan. Goodrich has been documenting and responding to the seasons on their plot of land in Somerset. “I feel very fortunate to have made this connection,” she says. “Dan and Huw are letting me slowly absorb the space and respond to the elements within it. The project will take over a year, but already it has pushed my work into new directions. It’s these encouragements that help me nurture my practice and the new ideas I constantly have.”

Words By Nell Card